One Step Up #40

This week, we look at RedBull, Shopify & Zapier, the Archegos meltdown, Amazon's ad business, some of Buffett's earliest investment write ups, understanding volatility/risk and more

The Mythology of Red Bull

My favourite bits:

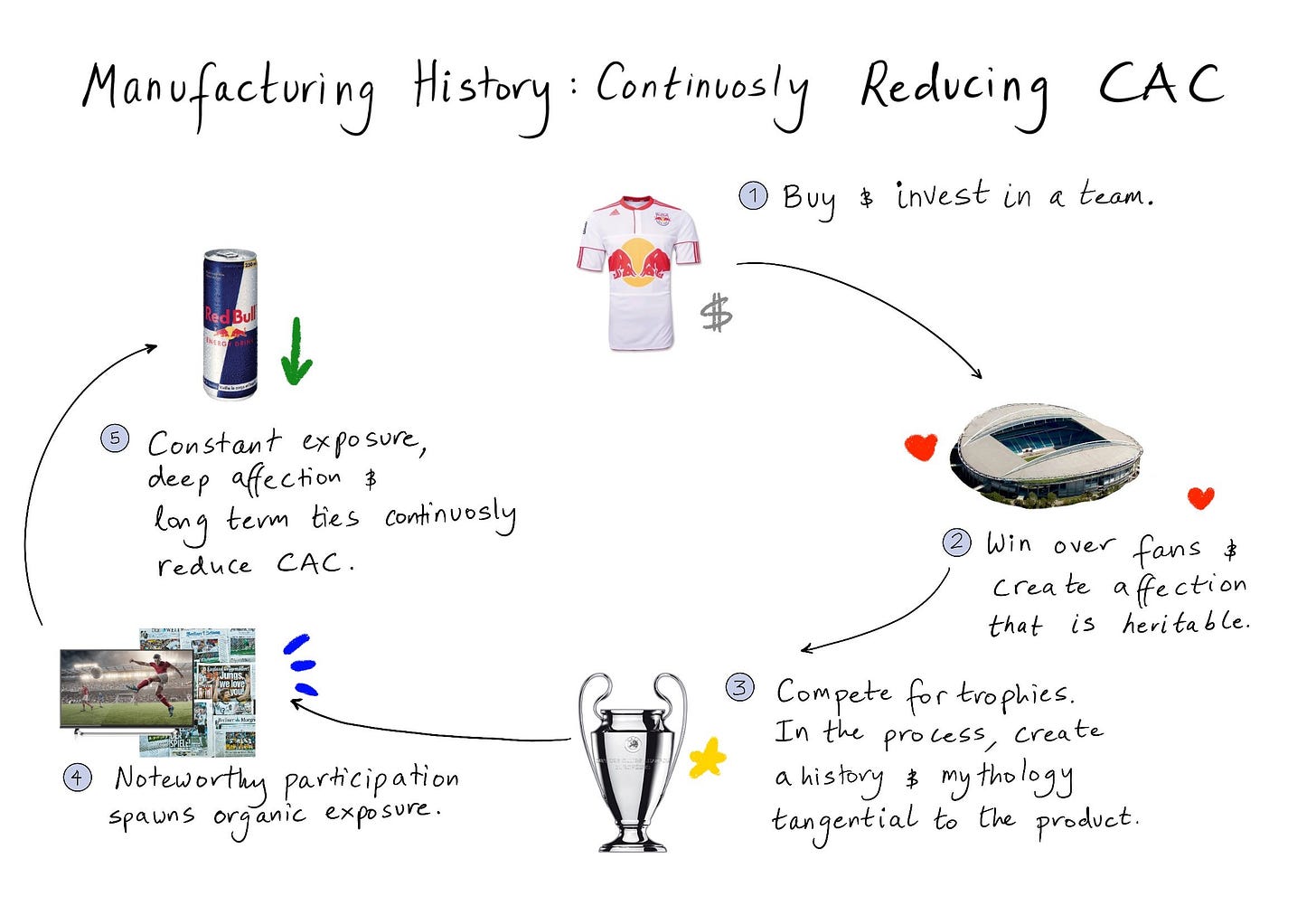

RedBull itself makes NOTHING - everything is outsourced (the drinks, apparel, clothing etc.)

It is fundamentally a marketing company (compared to Coca-Cola, they spend 4x more (as a % of revenue) on marketing/advertising

It invests in “creating history” by owning distribution channels. How? See below.

Two long-form business breakdowns to read this week:

Inside Archegos’s Epic Meltdown

WSJ article in the link above. A good thread below highlighting the intricacies in a simpler manner:

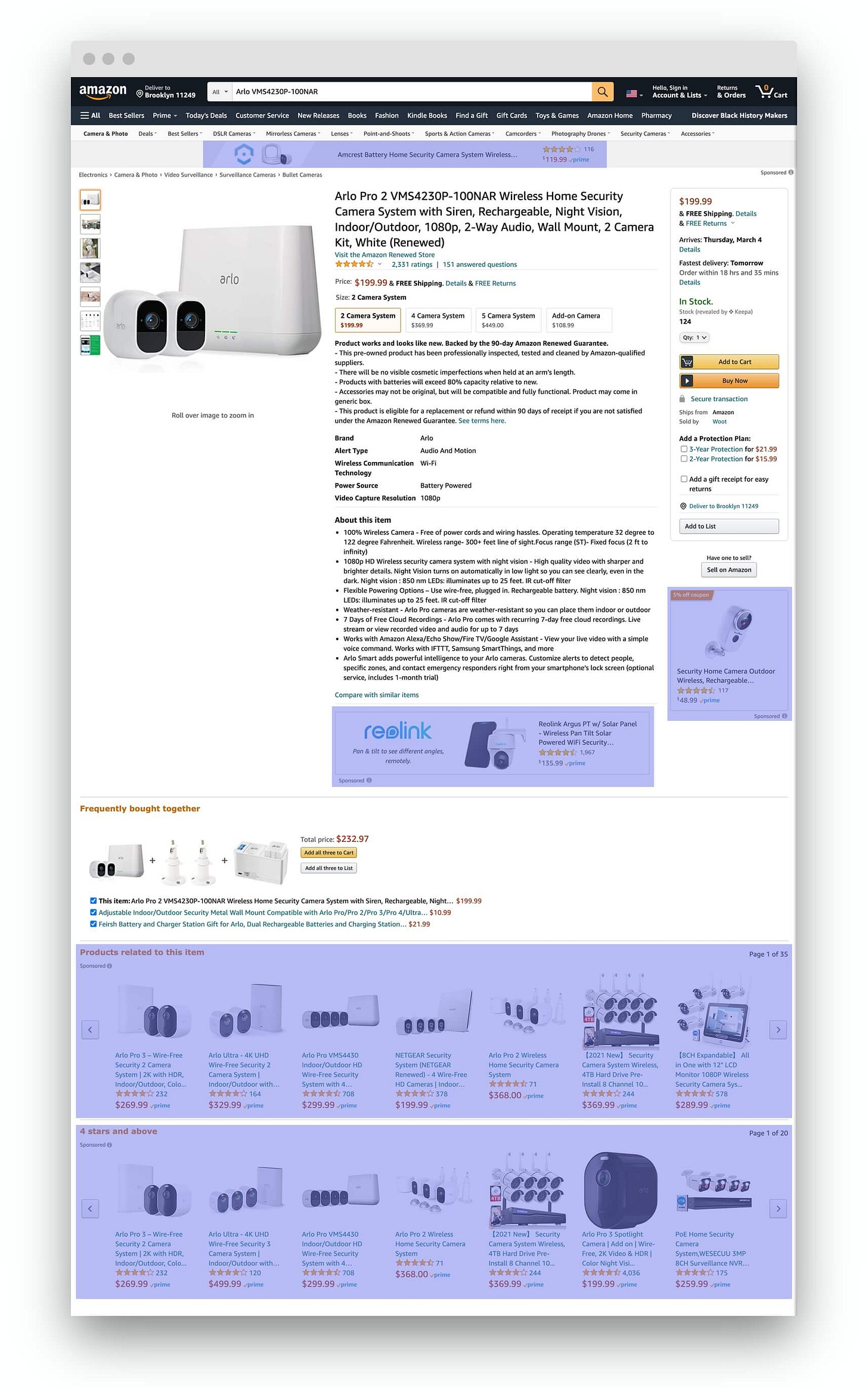

Amazon’s “Other Sales” line item on their income statement includes sales not otherwise included above, such as certain advertising services and our co-branded credit card agreements.

2014: $1.3 bn

2020: $21.5 bn

eBay followed suite. So did Walmart. I don't think anyone needs to be reminded just how great a business online advertising is.

Over the past year, “Sponsored products related to this item,” “Four stars and above” and “Brands related to this category on Amazon” advertising sections have all but replaced organic “Customers who bought this item also bought” and “Customers who viewed this item also viewed” suggestions. The last remaining recommendation functionality is “Frequently bought together.” Everything else on the product page, including additional display advertising, is an ad.

Warren Buffett’s 1950s ”The Security I Like Best” articles

Main takeaway: how to write a concise and compelling investment thesis in a page without diluting the quality.

Companies featured:

GEICO

Western Insurance Securities

Home Protective Co.

Oil and Gas Property Management

Read this thread to better understand volatility, risk, and the relationship between the two

Five levels of the game:

Apprentice — learning the game

Expert — mastering the game you were taught

Professional — making the game you were taught fit your own strengths and weaknesses

Master — changing the game you play as part of your own self-expression and operating at scale

Steward — becoming part of the playing field itself and mentoring the next generation

Why Your Mentors Seem Less Impressive Over Time

People who have been around the field for a while become increasingly disenchanted with their old mentors and talk about how they used to have good insights but now mostly recycle the same things, their best stuff was their earlier stuff, etc.

It often leads to a kind of retroactive downgrade of the mentor’s value, probably through a “curse of knowledge” effect where, once you know something, it’s hard to put yourself back in the shoes of someone who doesn’t know, and see how valuable being taught these things was, and how non-obvious they used to be to you.

In the early days, there’s lots of ‘low hanging-fruit’ insights and concepts to be picked from the mentor. Basically, your mind is being updated rapidly as you download knowledge from various sources.

At some point, the learning curve starts to level off, and while you may keep improving for the rest of your life, the rate of change is much lower.

Skill is non-linear: it can be just as hard, or likely harder, to go the last 10% of the way as it is to go the first 90%, since by that point the insights logically have to be harder to uncover and sources of progress have to be more difficult to tap.

But it’s that last little bit that makes a difference if you’re in a field where you’re competing against other people who probably also went through a similar progression.

If everyone can fairly easily and rapidly get through the first 90%, what will separate the wheat from the chaff will be mostly found in that last, harder-to-get, 10%.

So if we look at you and your mentor during the period relevant to your own progress, they start way ahead of you, but you rapidly catch up a good fraction of the way.

They may keep improving, but the rate at which they keep getting better usually won’t be nearly as fast as the rate that you’re improving at during the early part of the curve.

So the difference between the two lines becomes much smaller, and even if the remaining delta makes all the difference in performance (ie. even if many investors are 80% of the way to Buffett, it’s the other 20% that makes Buffett stand out), it still means that you can’t possibly get as much out of them as you could at first. The low-hanging fruits have all been picked.

This is why you get “mentor fatigue”.

Till next time.

In life the challenge is not so much to figure out how best to play the game; the challenge is to figure out what game you’re playing.